https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/

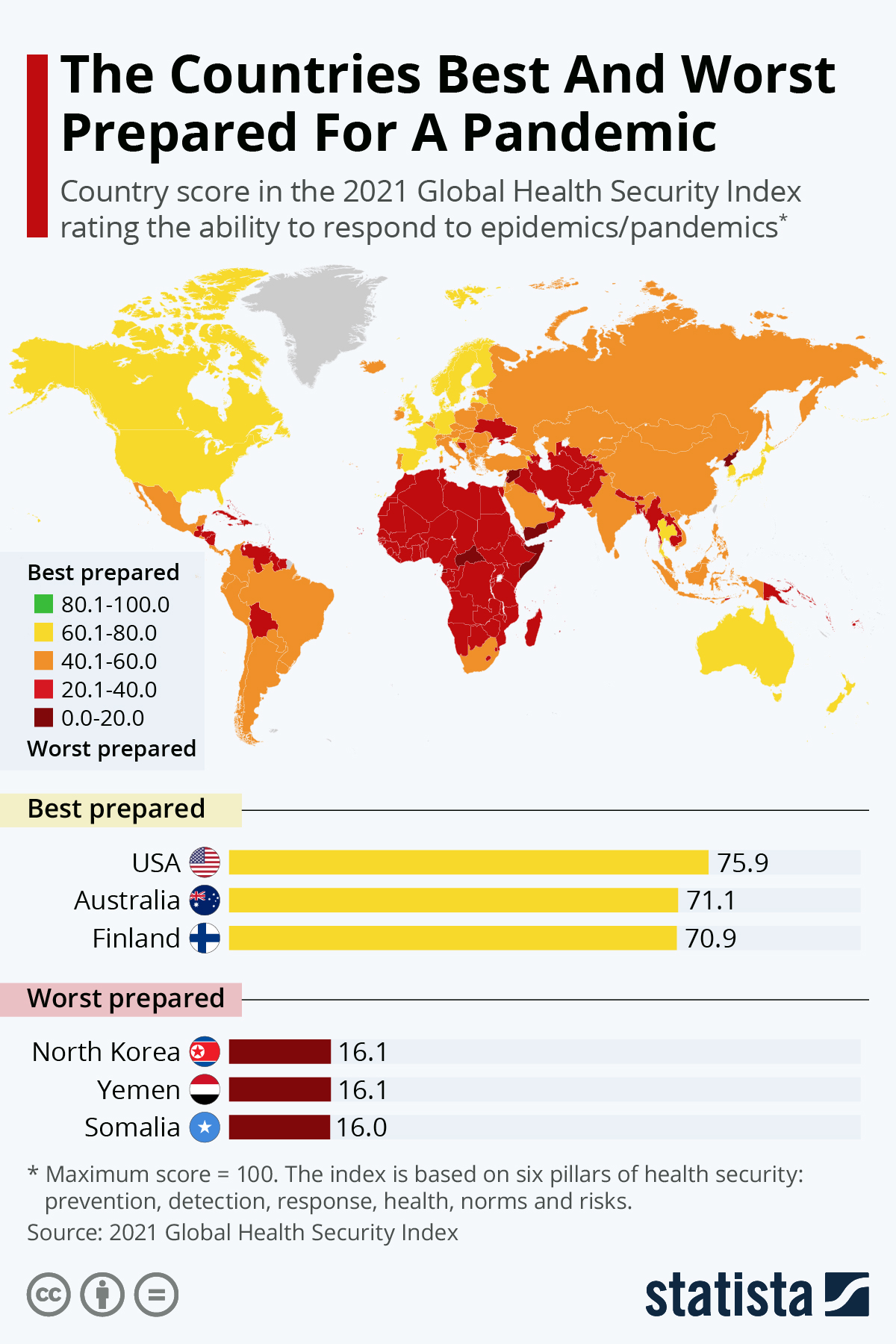

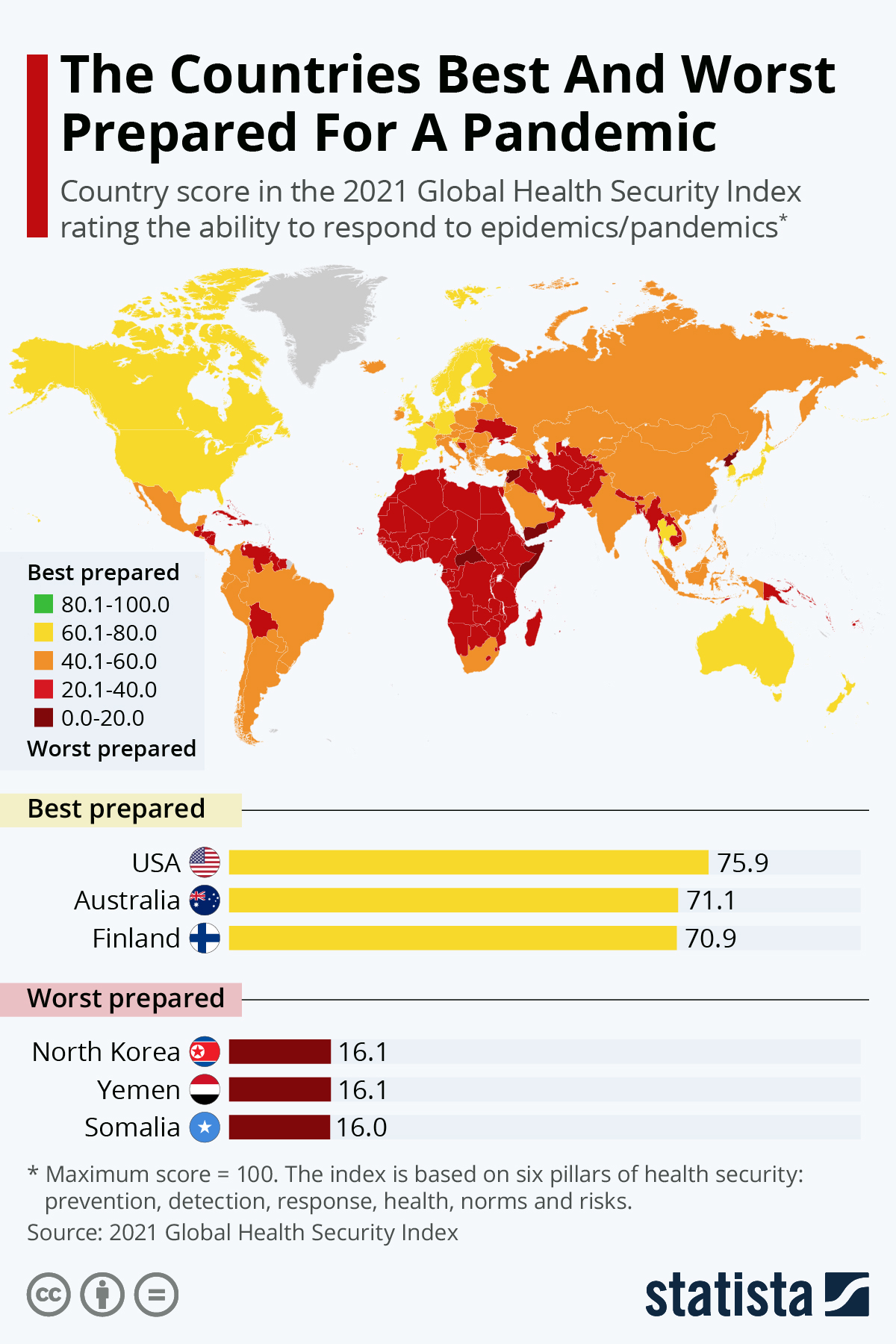

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

World Health Organization recommends people take simple precautions against virus to reduce exposure and transmission

Justin McCurry

Mon 27 Jan 2020 09.19 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2020/jan/27/coronavirus-how-to-protect-yourself-from-infection

A Chinese man wears a protective mask, goggles and coat as he stands in a nearly empty street during the Chinese New Year holiday in Beijing

A Chinese man wears a protective mask, goggles and coat during the lunar new year holiday in Beijing. Health authorities are urging people to take precautions against the spread of the coronavirus. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

The spread of the coronavirus across China and to at least 10 other countries including the US, South Korea and Japan has prompted experts and health authorities to offer advice on how to reduce the chances of contracting the illness.

All but four of the 80 reported deaths so far have been recorded in Hubei province where the outbreak started. Experts have warned, however, that about 100,000 people may already be infected – far more than the 2,700 cases reported by China’s National Health Commission in China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

What is the coronavirus and how worried should we be?

Read more

The World Health Organisation is recommending that people take simple precautions to reduce exposure to and transmission of the virus, for which there is no specific cure or vaccine.

The UN agency advises people to:

Frequently wash their hands with an alcohol-based hand rub or warm water and soap

Cover their mouth and nose with a flexed elbow or tissue when sneezing or coughing

Avoid close contact with anyone who has a fever or cough

Seek early medical help if they have a fever, cough and difficulty breathing, and share their travel history with healthcare providers

Avoid direct, unprotected contact with live animals and surfaces in contact with animals when visiting live markets in affected areas

Avoid eating raw or undercooked animal products and exercise care when handling raw meat, milk or animal organs to avoid cross-contamination with uncooked foods

Despite a surge in sales of face masks in the aftermath of the coronavirus outbreak, experts are divided over whether they can prevent transmission and infection of the airborne disease.

There is some evidence to suggest that masks can help prevent hand-to-mouth transmissions, given the large number of times people touch their faces – 23 times an hour, according to one study.

Dr David Carrington, of St George’s, University of London, told BBC News that “routine surgical masks for the public are not an effective protection against viruses or bacteria carried in the air”, because they were too loose, had no air filter and left the eyes exposed.

Masks could, however, help lower the risk of contracting a virus through the “splash” from a sneeze or a cough and offer some protection against hand-to-mouth transmissions, he said.

The consensus appears to be that wearing a mask can limit – but not eliminate – the risks, provided they are used correctly. That means securing them over the mouth, chin and nose, using the bendable metal strip at the top to keep it snug against the contours of the nose.

Experts say the best way to avoid germs, with coronavirus and other airborne illnesses, is to wash your hands thoroughly and frequently, try not to touch your face or eyes and avoid contact with people displaying symptoms.

WHO experts advise against wearing gloves on the basis that hand-washing is more important and people wearing gloves are less likely to wash their hands.

Why we should be skeptical of China’s coronavirus quarantine

As a historian of epidemics, I’m not optimistic it will turn out well

By Howard Markel

Howard Markel is the George E. Wantz distinguished professor of the history of medicine, a professor of pediatrics and communicable diseases, and the director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan. He is the author of “Quarantine!” and “When Germs Travel.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/why-we-should-be-skeptical-of-chinas-coronavirus-quarantine/2020/01/24/51b711ca-3e2d-11ea-8872-5df698785a4e_story.html

The new respiratory coronavirus, first detected in Wuhan, China, last month, is like most germs: It travels. It has jumped to Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, the southern Chinese province of Guangdong (home to SARS in 2003) and across borders to Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Japan, and even Seattle and Chicago. At this writing, more than 800 people have contracted it, and 26 have died.

To combat the contagion, the Chinese government has taken the extraordinary step of quarantining the city of Wuhan, as well as neighboring districts and cities. The borders are sealed, and all transportation out is blocked. Officials closed the public transportation systems. Friday morning, more than 35 million people woke up facing aggressive curtailments of their freedom.

Having spent my medical and academic career studying these issues, I am astounded by what is already the single largest quarantine in recorded history. As a physician, I cannot yet give a prognosis of how all this will work out. But as a historian of quarantines and epidemics — one who has read, seen or written similar sad stories too many times — I am not terribly optimistic it will turn out well.

China is in a real bind. If Beijing doesn’t act — or delays reporting on the situation, as officials did for five long months during the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic of 2002-2003 — then the virus will spread quickly and, if it proves especially lethal, could kill many more people than it already has. China will also incur international blame, economic sanctions or worse. Doing nothing is not an option in an era when information, fear and gossip travel at the speed of electrons and the public invariably demands action from leaders.

On the other hand, by taking the draconian step of closing down densely populated urban areas, China can hope only to diminish the coronavirus’s spread, knowing full well that some additional infections, or many, will inevitably occur. It takes just a few cases to spread outside the Chinese quarantine zone before critics say it has failed. As Lawrence O. Gostin, a public health law professor at Georgetown, has, for example, already said, “It’s very unlikely to stop the progressive spread.”

The U.S. has stopped Ebola before. But it may never repeat that success.

It’s possible that this coronavirus may not be highly contagious, and it may not be all that deadly. We also do not know yet how many people have mild coronavirus infections but have not come to medical attention, especially because the illness begins with mild to moderate respiratory tract symptoms, similar to those of the common cold, including coughing, fever, sniffles and congestion. Based on data from other coronaviruses, experts believe the incubation period for this new coronavirus is about five days (the range runs from two to 14 days), but we do not yet know how efficiently this coronavirus spreads from infected person to healthy person. And because antibodies for coronavirus do not tend to remain in the body all that long, it is possible for someone to contract a “cold” with coronavirus and then, four months later, catch the virus again.

The case fatality rate, a very important statistic in epidemiology, is calculated by dividing the number of known deaths by the number of known cases. At present, the virus appears to have a fatality rate of about 3 percent, which mirrors that of the influenza pandemic of 1918.

But what if there are 100,000 Chinese citizens in Wuhan with mild infections that we do not know about? That would lower the case fatality rate to a mere 0.02 percent, which comes closer to seasonal flu death rates. If that’s the case, a major disruption like the Chinese quarantine would seem foolish and cost a fortune in terms of public health efforts, interrupted commerce, public dissonance, trust, good will and panic.

Even open societies such as the United States have stringent laws regarding quarantine during epidemics, but they are rarely used because they are so poorly tolerated by citizens. Nevertheless, Americans have a long history of misapplying the quarantine. Russian Jewish immigrants in New York City in 1892, San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1900, and more recently gay men and Haitians in the early years of the AIDS epidemic were all stigmatized, isolated and blamed for the spread of contagious diseases. In many instances, some of these “undesirable” groups were inappropriately quarantined; their health needs were routinely ignored; and some even contracted deadly diseases while in isolation.

None of this is to say that extreme quarantines can’t be effective. In 2004, I attended an international meeting focused on examining the public health response to the SARS epidemic the year before. One panel featured the health officers of Singapore, Beijing, Hong Kong and Toronto. Singapore and Beijing had imposed the harshest and most restrictive quarantines and had the best results in terms of decreasing the disease’s spread and rates of morbidity and mortality. Hong Kong, and to a much greater extent Toronto — both open societies — applied far more lax containment policies and experienced much greater spread of the disease and more deaths.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean autocratic nations, such as China, are better equipped to contain contagious diseases. When the public trusts leaders and health authorities, it is easier to establish wide-scale cooperation, clear lines of communication and appropriate, humane health care. Civic-minded, community-wide, voluntary disease containment and mitigation efforts — such as those adopted in Mexico City during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, when officials inspired buy-in from the public to enact bans on social gatherings, school closures, isolation of the ill and at-home quarantines for those suspected of having contact with sick people — have been shown to work well. That is certainly the prescription I would write, and it’s not one that extreme measures are likely to engender.

Microbes, as agents of illness and death, are the ultimate social leveler. They bind us and, when transmitted through a filter of fear, have the power to divide. China has deemed this contagious disease to be too dangerous, or poorly understood, to take any chances with the public’s health. But the country also has a moral imperative to provide safe and compassionate medical care for those confirmed or suspected to be infected by the coronavirus. Equitable and fair attention to adequate housing; individual rights; economic and recreational needs; cultural and religious beliefs and practices; Internet, telecommunications and other connectivity; and the emotional, psychological and social difficulties patients invariably experience in isolation are as essential to a quarantine effort as the hue and cry of rounding up victims. Such human considerations cannot, of course, eradicate the many problems caused by the experience of quarantine, but they can reduce those burdens.

This is the question that will shape the story of this coronavirus outbreak: Not whether China will quarantine other cities or impose still more draconian edicts, but whether it is up to the enormous task of caring for those separated from the rest of society.

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

World Health Organization recommends people take simple precautions against virus to reduce exposure and transmission

Justin McCurry

Mon 27 Jan 2020 09.19 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2020/jan/27/coronavirus-how-to-protect-yourself-from-infection

A Chinese man wears a protective mask, goggles and coat as he stands in a nearly empty street during the Chinese New Year holiday in Beijing

A Chinese man wears a protective mask, goggles and coat during the lunar new year holiday in Beijing. Health authorities are urging people to take precautions against the spread of the coronavirus. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

The spread of the coronavirus across China and to at least 10 other countries including the US, South Korea and Japan has prompted experts and health authorities to offer advice on how to reduce the chances of contracting the illness.

All but four of the 80 reported deaths so far have been recorded in Hubei province where the outbreak started. Experts have warned, however, that about 100,000 people may already be infected – far more than the 2,700 cases reported by China’s National Health Commission in China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

What is the coronavirus and how worried should we be?

Read more

The World Health Organisation is recommending that people take simple precautions to reduce exposure to and transmission of the virus, for which there is no specific cure or vaccine.

The UN agency advises people to:

Frequently wash their hands with an alcohol-based hand rub or warm water and soap

Cover their mouth and nose with a flexed elbow or tissue when sneezing or coughing

Avoid close contact with anyone who has a fever or cough

Seek early medical help if they have a fever, cough and difficulty breathing, and share their travel history with healthcare providers

Avoid direct, unprotected contact with live animals and surfaces in contact with animals when visiting live markets in affected areas

Avoid eating raw or undercooked animal products and exercise care when handling raw meat, milk or animal organs to avoid cross-contamination with uncooked foods

Despite a surge in sales of face masks in the aftermath of the coronavirus outbreak, experts are divided over whether they can prevent transmission and infection of the airborne disease.

There is some evidence to suggest that masks can help prevent hand-to-mouth transmissions, given the large number of times people touch their faces – 23 times an hour, according to one study.

Dr David Carrington, of St George’s, University of London, told BBC News that “routine surgical masks for the public are not an effective protection against viruses or bacteria carried in the air”, because they were too loose, had no air filter and left the eyes exposed.

Masks could, however, help lower the risk of contracting a virus through the “splash” from a sneeze or a cough and offer some protection against hand-to-mouth transmissions, he said.

The consensus appears to be that wearing a mask can limit – but not eliminate – the risks, provided they are used correctly. That means securing them over the mouth, chin and nose, using the bendable metal strip at the top to keep it snug against the contours of the nose.

Experts say the best way to avoid germs, with coronavirus and other airborne illnesses, is to wash your hands thoroughly and frequently, try not to touch your face or eyes and avoid contact with people displaying symptoms.

WHO experts advise against wearing gloves on the basis that hand-washing is more important and people wearing gloves are less likely to wash their hands.

Why we should be skeptical of China’s coronavirus quarantine

As a historian of epidemics, I’m not optimistic it will turn out well

By Howard Markel

Howard Markel is the George E. Wantz distinguished professor of the history of medicine, a professor of pediatrics and communicable diseases, and the director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan. He is the author of “Quarantine!” and “When Germs Travel.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/why-we-should-be-skeptical-of-chinas-coronavirus-quarantine/2020/01/24/51b711ca-3e2d-11ea-8872-5df698785a4e_story.html

The new respiratory coronavirus, first detected in Wuhan, China, last month, is like most germs: It travels. It has jumped to Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, the southern Chinese province of Guangdong (home to SARS in 2003) and across borders to Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Japan, and even Seattle and Chicago. At this writing, more than 800 people have contracted it, and 26 have died.

To combat the contagion, the Chinese government has taken the extraordinary step of quarantining the city of Wuhan, as well as neighboring districts and cities. The borders are sealed, and all transportation out is blocked. Officials closed the public transportation systems. Friday morning, more than 35 million people woke up facing aggressive curtailments of their freedom.

Having spent my medical and academic career studying these issues, I am astounded by what is already the single largest quarantine in recorded history. As a physician, I cannot yet give a prognosis of how all this will work out. But as a historian of quarantines and epidemics — one who has read, seen or written similar sad stories too many times — I am not terribly optimistic it will turn out well.

China is in a real bind. If Beijing doesn’t act — or delays reporting on the situation, as officials did for five long months during the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic of 2002-2003 — then the virus will spread quickly and, if it proves especially lethal, could kill many more people than it already has. China will also incur international blame, economic sanctions or worse. Doing nothing is not an option in an era when information, fear and gossip travel at the speed of electrons and the public invariably demands action from leaders.

On the other hand, by taking the draconian step of closing down densely populated urban areas, China can hope only to diminish the coronavirus’s spread, knowing full well that some additional infections, or many, will inevitably occur. It takes just a few cases to spread outside the Chinese quarantine zone before critics say it has failed. As Lawrence O. Gostin, a public health law professor at Georgetown, has, for example, already said, “It’s very unlikely to stop the progressive spread.”

The U.S. has stopped Ebola before. But it may never repeat that success.

It’s possible that this coronavirus may not be highly contagious, and it may not be all that deadly. We also do not know yet how many people have mild coronavirus infections but have not come to medical attention, especially because the illness begins with mild to moderate respiratory tract symptoms, similar to those of the common cold, including coughing, fever, sniffles and congestion. Based on data from other coronaviruses, experts believe the incubation period for this new coronavirus is about five days (the range runs from two to 14 days), but we do not yet know how efficiently this coronavirus spreads from infected person to healthy person. And because antibodies for coronavirus do not tend to remain in the body all that long, it is possible for someone to contract a “cold” with coronavirus and then, four months later, catch the virus again.

The case fatality rate, a very important statistic in epidemiology, is calculated by dividing the number of known deaths by the number of known cases. At present, the virus appears to have a fatality rate of about 3 percent, which mirrors that of the influenza pandemic of 1918.

But what if there are 100,000 Chinese citizens in Wuhan with mild infections that we do not know about? That would lower the case fatality rate to a mere 0.02 percent, which comes closer to seasonal flu death rates. If that’s the case, a major disruption like the Chinese quarantine would seem foolish and cost a fortune in terms of public health efforts, interrupted commerce, public dissonance, trust, good will and panic.

Even open societies such as the United States have stringent laws regarding quarantine during epidemics, but they are rarely used because they are so poorly tolerated by citizens. Nevertheless, Americans have a long history of misapplying the quarantine. Russian Jewish immigrants in New York City in 1892, San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1900, and more recently gay men and Haitians in the early years of the AIDS epidemic were all stigmatized, isolated and blamed for the spread of contagious diseases. In many instances, some of these “undesirable” groups were inappropriately quarantined; their health needs were routinely ignored; and some even contracted deadly diseases while in isolation.

None of this is to say that extreme quarantines can’t be effective. In 2004, I attended an international meeting focused on examining the public health response to the SARS epidemic the year before. One panel featured the health officers of Singapore, Beijing, Hong Kong and Toronto. Singapore and Beijing had imposed the harshest and most restrictive quarantines and had the best results in terms of decreasing the disease’s spread and rates of morbidity and mortality. Hong Kong, and to a much greater extent Toronto — both open societies — applied far more lax containment policies and experienced much greater spread of the disease and more deaths.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean autocratic nations, such as China, are better equipped to contain contagious diseases. When the public trusts leaders and health authorities, it is easier to establish wide-scale cooperation, clear lines of communication and appropriate, humane health care. Civic-minded, community-wide, voluntary disease containment and mitigation efforts — such as those adopted in Mexico City during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, when officials inspired buy-in from the public to enact bans on social gatherings, school closures, isolation of the ill and at-home quarantines for those suspected of having contact with sick people — have been shown to work well. That is certainly the prescription I would write, and it’s not one that extreme measures are likely to engender.

Microbes, as agents of illness and death, are the ultimate social leveler. They bind us and, when transmitted through a filter of fear, have the power to divide. China has deemed this contagious disease to be too dangerous, or poorly understood, to take any chances with the public’s health. But the country also has a moral imperative to provide safe and compassionate medical care for those confirmed or suspected to be infected by the coronavirus. Equitable and fair attention to adequate housing; individual rights; economic and recreational needs; cultural and religious beliefs and practices; Internet, telecommunications and other connectivity; and the emotional, psychological and social difficulties patients invariably experience in isolation are as essential to a quarantine effort as the hue and cry of rounding up victims. Such human considerations cannot, of course, eradicate the many problems caused by the experience of quarantine, but they can reduce those burdens.

This is the question that will shape the story of this coronavirus outbreak: Not whether China will quarantine other cities or impose still more draconian edicts, but whether it is up to the enormous task of caring for those separated from the rest of society.

No comments:

Post a Comment